Heather and Bryan had the pleasure of traveling to New Orleans, Louisiana for a week in the spring of 2019. As with any good history nerds, much of their trip was devoted to seeing the unique historical sights of the lower Mississippi. This post begins a series on their experiences of how the many facets of New Orleans history are interpreted for the public.

While visiting New Orleans on our spring break last week, Bryan and I made a day trip west of the city to see two of Louisiana’s most famous plantations: Oak Alley in Vacherie and Whitney in Wallace. Although the two sites are only a 15-minute drive from one another, the plantations are nonetheless worlds apart when it comes to how they grapple with our nation’s most painful and contentious history: that of slavery.

At their agricultural zeniths, both Oak Alley and Whitney were titans of the lucrative Gulf Coast sugar business. Both plantations relied on slave labor to plant, cultivate, and reap acres of sugarcane stalks each growing season. Through backbreaking and dangerous manual labor, the cane was then processed into refined sugar which was packaged for sale to wealthy buyers. Over the decades, both plantations fell into disuse and disrepair until they were renovated by outside buyers. Today, these plantations are preserved as historical sites visited by tourists from across the U.S. and around the world.

For Bryan and me, visiting these two sites back to back on the same day was very purposeful. We had heard of Oak Alley’s track record of being one of the many ‘moonlight, magnolias, and happy slaves’ historical sites. We had also heard tell of its recent attempts in the last few years at a more conscientious interpretation of slavery and were curious to see how they held up to scrutiny. Most important to both of us was visiting Whitney; I had read a fascinating New York Times article about the creation of the Whitney Plantation museum when I was in college and had kept it in mind as a place I’d like to see someday. Because Whitney is in large part a response to more popular tourist destination plantations, we decided to see Oak Alley in the morning and then Whitney after lunch.

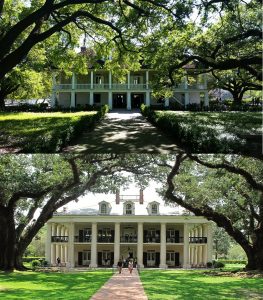

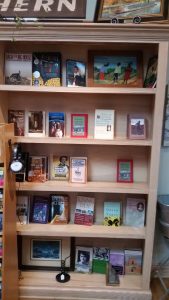

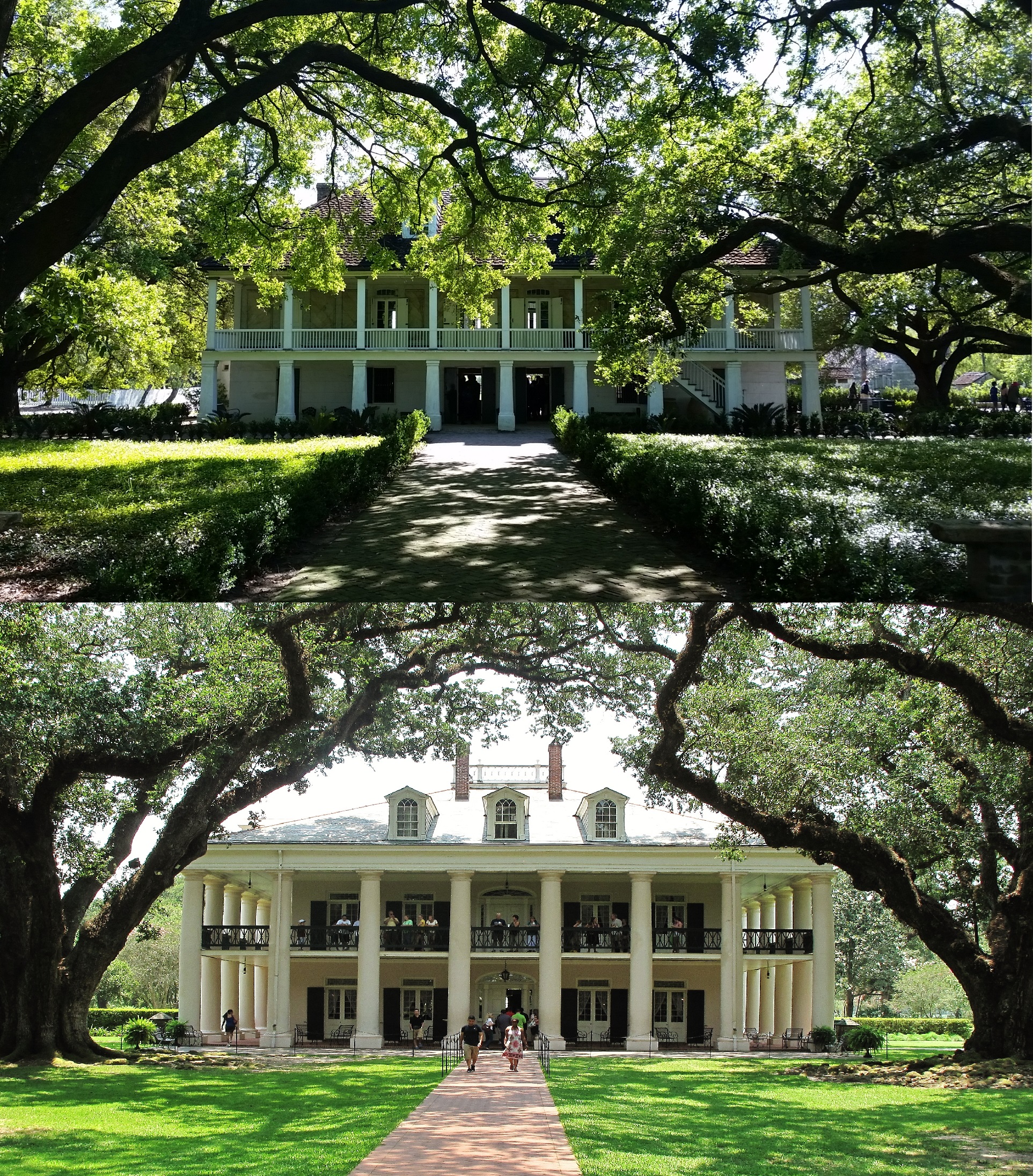

The first thing you notice when pulling up to Oak Alley is its eponymous and iconic row of live oaks leading up to the Big House. It’s a breathtaking view, and largely to thank for the site being as popular as it is. After you purchase your ticket (adults are $25.00 a piece), the “Slavery at Oak Alley” exhibit is the first sight you come across; it is also, admirably, listed before the Big House on the introductory panels at the entrance to the plantation. Included in the slavery exhibit are several reconstructed slave cabins with furnishings, chicken coops, and laundry kettles. Each cabin includes a small sign with interpretive text detailing the day-to-day lives of the plantation’s enslaved laborers. The signs repeatedly remind visitors of the cruelties of life under slavery; at least in the slavery exhibit, there was no ‘happy slave’ mythology to be found. Outside the slavery exhibit, the plantation gift shop included a bookshelf dedicated to

the history of slavery and freedmen: another refreshing surprise.

Despite these pleasant surprises, though, Oak Alley remains shackled to a whitewashed interpretation of its history. In the Big House, tours are lead by docents in antebellum hoop skirts and guests can purchase three flavors of mint juleps to sip on the restaurant patio. The biggest problem, though, is that the “Slavery at Oak Alley” exhibit has none of the glamour of the Big House. Its humbleness makes it easy for tourists who are focused on capturing Kodak moments of the plantation’s iconic architecture and landscaping to bypass it. In short, at Oak Alley the slavery interpretation is an opt-in experience.

Just 10 miles down the road, though, visitors can find a slavery interpretation that is anything but opt-in. There is nothing elective about dealing with the tough stuff at Whitney. At this site that one reporter goes so far as to call “America’s Auschwitz,” no matter where you turn, the hard truths are staring right back at you. Even before you meet your guide and begin the tour through the grounds ($23.00 per adult), you are given a

lanyard to serve as your ticket during your stay. On each lanyard is a photo of one of Whitney’s famous clay sculptures that depict the children who were enslaved on the plantation; on the reverse side is the information we know about that person’s life and how old they lived to be. The site leans heavily on the oral histories recorded by the Depression Era Federal Writers’ Project as well as on historical records kept by the plantation. Throughout the grounds of the plantation, memorials to the enslaved dominate: the Wall of Honor lists the names of all those known to have been enslaved during Whitney’s operation, the Allées Gwendolyn Midlo Hall lists the 107,000 names recorded in the Louisiana Slave Database, and the Field of Angels is dedicated to 2,200 enslaved Louisiana children who died before the age of three. Where Oak Alley has an atmosphere of admiration and delight, Whitney’s is decidedly solemn and reflective.

Our tour at Whitney was well-researched and informative. Our guide, Ali, drew clear connections between racism and capitalism throughout history and between slavery and its echoes of poverty, colorism, and mass incarceration in the present. He laid out the naked truths of slavery and its repercussions with authority; there were no frills and no theatrics, and we came away with a sense of gravity. From the slave cabins to the Big House, at no point were we given the luxury of ignoring the unpleasant truths of the past. For those who are uninitiated into the harsh realities of slavery history, the tour would no doubt be uncomfortable. We got the sense, though, that Whitney may be more of a place of pilgrimage than learning; those in our group were quiet and respectful and the eager faces of Oak Alley were nowhere to be found.

While it was refreshing to see the progress being made at Oak Alley, the contrast with Whitney was stark. Oak Alley may have made a nod to interpreting slavery and its atrocities, but Whitney looked it square in the face and refused to back down. We were grateful to have had the chance to see both, and we look forward to seeing how the two institutions continue to evolve in response to the changing backdrop of current events.

One reply on “Interpreting the Big Easy: Wrestling with the Past at Oak Alley and Whitney Plantations”

Thank you so much for such a thoughtful and conscientious article. It’s very helpful as one researching where I want to go on a brief trip to New Orleans. I’m excited to see if much has changed in the last five years.